St. Leonard’s History

St. Leonard’s Church has a rich history

The Parish of Bengeo is somewhat unusual in possessing two churches in regular use. Saint Leonard’s built shortly after the Norman Conquest served as the parish church until 1855 when this role passed to the new and much larger church of Holy Trinity designed by Benjamin Ferrey. However, for the latter part of the 19th and the early part of the 20th century, Bengeo possessed no less than five churches.

Christ Church in Port Vale served the area that is now known as Lower Bengeo and was made redundant in 1968 when certain features were transferred to Holy Trinity. Saint Mary’s Chapel of Ease served the community of Tonwell and has now been incorporated into the church school there, while Saint Michael’s at Waterford was made into a separate parish about a 100 years ago.

Let us begin our tour of Saint Leonard’s.

The entrance – medieval mass dial

The small brick entrance porch is the single addition to the fabric of the original church and dates from Georgian times.

For most of the church’s life, the South door would have opened directly to the outside. Moreover, the South doorway is cited as one of the Saxon features of the church with jambs constructed of irregular stone blocks laid in alternate directions.

To the left of the door when viewed from the porch, can be seen a mass dial cut into the stone to remind worshippers when services would take place. The gnomon or pointer which showed the time by casting its shadow on the dial has long since disappeared but the incisions on the dial clearly indicate the early morning as the time of the principal mass. The workmanship is quite crude and indeed these mass dials are often called scratch dials for obvious reasons. Close inspection of the surrounding stonework reveals other even rougher dials and a consecration cross.

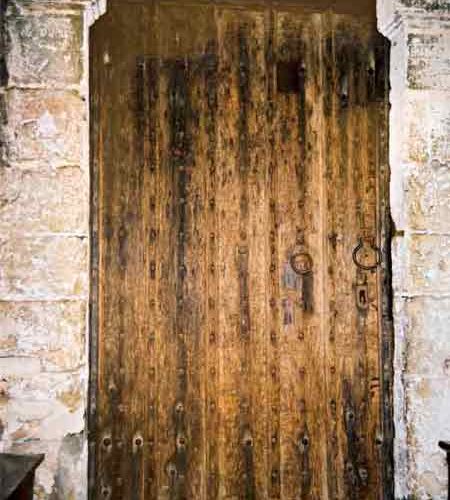

The South door: Exterior aspect and internal handle

One of the jewels of the church is the oak door. It is exceptional to find such an ancient door still in use. It consists of three sections clamped together by iron bolts: the external face is 14th century and although it was exposed to the elements for centuries, we can still appreciate its simple linen fold design.

Appearances are deceptive! The interior handle is not of ancient origin. Underneath and to the sides of the handle is the inscription: 20th June 1897!

The nave

The nave is remarkable for the simplicity of its design and indeed its exposed roof timbers may remind us of a Medieval tithe barn.

It is largely unchanged from when it was originally built-apart from the enlargement of the windows in the South wall that make it far lighter than it would have been previously-although we must not forget that they would have been glazed with stained glass. The raised area at the West end of the church was the base for the minstrel’s gallery which was only removed in 1879. The bowl of the font is Norman work and was rescued from a neighbouring garden in the 19th century. Presumably it had been taken from the church during the Commonwealth period.

When a visitor first enters the church, the eye is immediately drawn to the East window and the altar beyond the rounded chancel arch. Indeed this arch, which is one of the Saxon features of the church, appears relatively small in scale in comparison with the great West wall of the Nave. This serves to create the impression of the chancel as an area set apart for the celebration of the sacred mysteries of the Blessed Sacrament. In Medieval times, a rood beam fitted supporting the figures of the crucified Christ together with Saint Mary and Saint John would have reinforced this sense of apartness; indeed the sockets into which the beam are still clearly visible.

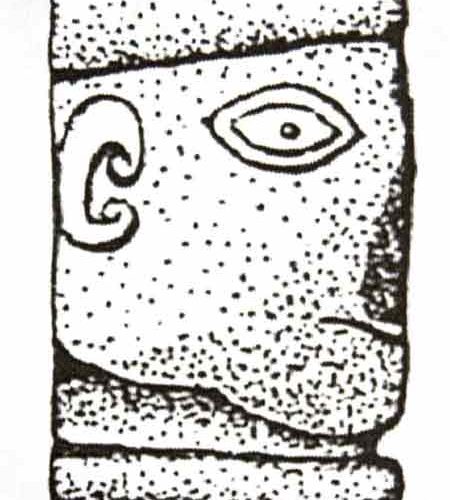

The nave guard

Consistent with the concept of the other-worldliness of the chancel is a particularly interesting feature of the chancel arch: the left hand capital. The primitive form of a face stares at the congregation and seems to be guarding the Holy of Holies. We can only speculate as to the intention of the Saxon mason.

The vertical lines of the pillars of the arch were damaged in the 18th century when stonework was hacked away to accommodate box pews for the Hall family of Goldings.

13th Century Wall Paintings

The Deposition from the Cross

This very early Medieval, probably 13th century, painting has something of the quality of an icon in which the artist presents a holy image to help us in our devotions.

Here the disciples lift down the body of Christ from the cross prior to its burial in the tomb belonging to Joseph of Arimathea.

Set against a plain background, the participants in the drama appear isolated in their grief. Yet at the same time, there is an overall impression of serenity in the depiction of our Lord’s body about to be gently lowered to the rocky outcrop of Golgotha which the artist outlines at the foot of the painting. At the top of the cross is a panel which originally read I.N.R.I., short for Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum (Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews). The golden halo encircling the head of Jesus contains 3 bars recalling the Holy Trinity.

To the left of the group, we see the Blessed Virgin Mary clasping the right hand of our Lord. She stands calm and collected but appears lost in thought as she regains physical contact with her Son. Other paintings of the same period make much of the fact that his body was returned to the mother who had so often held him in her arms. Joseph of Arimathea, a wealthy Jew, had been a secret follower of Jesus but he had now found the courage to ask Pilate for the body. As he was never canonised, he simply wears a flat Jewish cap without a halo. With his head pressed against our Lord’s chest as he prepares to take the weight, he creates the impression of a loving embrace.

The female figure to the right of the cross is almost certainly Mary Magdalene. She holds aloft 2 of the instruments of the Passion, a nail and pliers, which point to the wound in the palm of our Lord’s hand. The mysterious bearded figure on the extreme right occupies a position traditionally assigned to John, the beloved disciple. Certainly he is given a halo, but John is generally depicted as clean shaven. More probably the figure is that of Nicodemus, the lawyer, who visited Jesus by night and was present at the Crucifixion. He wears a look of bewilderment at the turn of events. His left hand is shown in two positions, stroking his beard in puzzlement and directing our gaze to the drama that is unfolding.

The composition invites us to contemplate a tragic scene but one invested with dignity, a moment of calm poised between the horror of Good Friday and the joy of Easter.

The walls

The Minet Wall Tablet

The neoclassical memorial in white marble on the North wall is by Joseph Nollekens, the finest British sculptor of the late 18th century.

Nollekens was the son of an artist in Antwerp and when he set up his studio in London, his work was so highly regarded, he included King George 111, Charles James Fox and William Pitt, the younger, among his sitters. Today a number of his works are displayed in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Daniel Minet and Rebecca Minet by Thomas Gainsborough

Reproduced by courtesy of the Society of Antiquaries.

Daniel Minet was a member of a distinguished Huguenot family who were refugees from persecution in France after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. As a young man, his grandfather Isaac had escaped across the Channel in a rowing boat and had gone on to make his fortune in a successful business career.

Daniel studied law at the Inner Temple, became Surveyor of Customs and a distinguished man of letters specialising in archaeology, a study at that time in its infancy. He was a member of the Society of Antiquaries and of the Royal Society. He married Rebecca Stert, daughter of a London merchant, in 1779 and they shared their time between homes in Bengeo and Grosvenor Street, Mayfair. They had their portraits painted by Gainsborough in around 1780.

The Paintings – Moses and Aaron

The arresting pair of oil paintings on the West wall date from the 18th century. They depict the commanding figures of Moses and his brother, Aaron, who together led the Israelites from their captivity in Egypt through the desert to the Promised Land. Moses bears the tablets of the Law known as the Ten Commandments while Aaron wears his priestly vestments and holds a censer in one hand and in the other his famous staff which according to the Biblical narrative sprouted with almond blossom.

The paintings by an unknown artist originally hung behind the altar on either side of the east window whose shape they replicate. In Christian tradition, both leaders are seen as prefiguring Christ and their depiction was much favoured in the 18th century as representing the twofold tenets of our faith: the Word and the Sacraments.

The Royal Coat of Arms

The Royal Coat of Arms on the North wall is that of George I and is dated 1719. It differs significantly from the royal Arms adopted by Queen Victoria which remains unchanged to this day. While the first quarter contains the familiar lions of England, the second with its fleur de lys reminds us of the historic claim of the British Crown to the French throne. The third quarter contains the harp of Ireland while the famous white horse of Hanover is prominent in the fourth quarter.

The coat of arms was probably originally sited above the chancel arch and would have reminded parishioners that the monarch had been anointed at his coronation and bore the title Defender of the Faith.

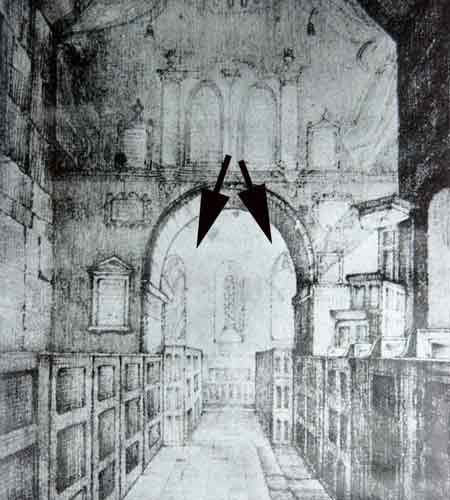

18th Century Interior

This view of the nave shows us how differently the church appeared with its 18th century furnishings. High box pews would have ensured that the congregation could be accommodated according to their social status with that of the Hall family from the Palladian mansion at Goldings occupying place of honour nearest both the altar and their family vault and monument. To the right of the chancel arch, there is a three-decker pulpit with prayer-desk, lectern and pulpit combined in one. The wall above the chancel arch is decorated with an ornate baroque decorative scheme featuring classical motifs and flowing swags incorporating texts such as the crede. On either side of the East window, the paintings of Moses and Aaron are in their original position. Wooden boarding conceals the roof timbers of the nave and adds to the overall effect which to modern eyes appears to reduce both the sense of space and of the building’s antiquity.

The Funeral Hatchments

Invariably diamond-shaped, hatchments were introduced into this country from Holland in the early 17th century. Painted on canvas, they were used to proclaim a death in a landed or titled family. They were emblazoned with the heraldic arms of the deceased and carried in procession at the funeral. They were then generally hung from the house front for a year before being placed in the parish church. This widespread practice began to fall into decline in the 1860s and most of the hatchments which once adorned our churches have long since perished. St Leonard’s is fortunate in retaining three fine examples.

The pair hanging on the South wall commemorate Admiral Thomas le Marchant Gosselin and his wife Sarah of Bengeo Hall. The admiral who was a national hero of the Napoleonic Wars outlived his wife by no less than 42 years. Both hatchments present the same shield but whereas Sarah’s is suspended by ribbons tied in love knots, her husband’s is surmounted by a crest and the striking head of an African wearing a gold earring. The fact that half the background of Sarah’s hatchment is coloured white tells us that she died before her husband.

The third hatchment hangs on the North wall and commemorates Sir Eric Mackay, 7th Baron Reay, a member of one of Scotland’s distinguished clans. He was a Scottish representative peer and died at Goldings which he was leasing from the Abel Smith family. The supporters are two soldiers wearing the colourful uniforms of the time. Each holds a musket armed with a bayonet in their outside hand. Above the shield, the coronet reminds us that Sir Eric was a baron.

The Bell

St Leonard’s has a single bell, inscribed “Praise the Lord 1636”. It was made by Robert Oldfield, a well-known bell founder in Hertford. This bell was removed to Holy Trinity Church when it took over duties as the parish church, but was returned at a later date. It is rung when services are held at the church.